Does your organization have a proactive employee retention strategy? Do you offer competitive compensation, performance-based incentives, and quality of life benefits? Does your HR department solicit employee feedback and strive to make your firm “a great place to work?”

Does your organization have a proactive employee retention strategy? Do you offer competitive compensation, performance-based incentives, and quality of life benefits? Does your HR department solicit employee feedback and strive to make your firm “a great place to work?”

That’s all well and good. But it’s not enough. There’s something…or rather, someone you may have overlooked—and that someone is your technical staff. Engineers, scientists, and IT professionals are not your average employees. They operate under a different set of rules, experiences, and motivational factors—distinct from operations, sales, marketing, finance, and other professional and administrative personnel.

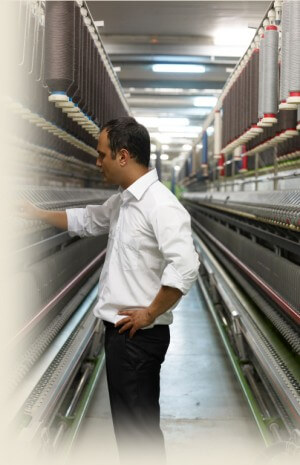

Technology workers require particular attention because they are vital to your company’s current and future competitiveness. Process improvement, product innovation, and business intelligence are all driven by people with technical backgrounds. Organizational consultant Gerald Ledford in his article, How to Keep Me–Retaining Technical Professionals, states “in many companies, science and technology has eclipsed marketing, finance and even sales as the critical employee segment.”

If you’re relying on the same retention programs that you use for everyone else, you may find your most valued employees heading for the exits. According to Ledford, “These [technical] professionals can create the franchise for company growth and are increasingly sought after by established corporations or pre-IPO start-ups.” With the current talent shortages in the global chemical and allied industries, you can be assured that your competitors are aggressively courting your technical talent. Are you providing enough of an incentive to keep them?

“So what if we lose a few tech pros. What’s the big deal?”

Well, consider the following issues, each of which is its own “big deal”:

Replacement cost. Replacing a technology worker isn’t cheap. Factor in the costs of recruiting, training, business interruption, and most critically, knowledge loss, and the hard dollar costs of replacement are substantial. When evaluating retention strategies, it can be very helpful to estimate replacement costs in order to determine an appropriate budget for retention initiatives. For instance, industry experts estimate the cost of replacing the average engineer at around $200K.

Market cost. High turnover in technical and scientific staff can have a potentially devastating impact on your company’s competitiveness and standing as a market leader. No one wants to join a sinking ship, and if attrition becomes significant, word will get out. At that point, attracting top-tier replacement talent will be far more difficult…and costly.

Knowledge transfer. When a technology worker walks out the door, odds are they’re walking into a competitor’s. While you may have non-competes and non-disclosures in place, the practical reality is that some (or potentially a significant amount) of competitive intelligence gets transferred.

Knowledge transfer. When a technology worker walks out the door, odds are they’re walking into a competitor’s. While you may have non-competes and non-disclosures in place, the practical reality is that some (or potentially a significant amount) of competitive intelligence gets transferred.

Loss of innovation. The most significant cost of losing technology professionals is the impact it can have on R&D and innovative thinking. Failing to remain competitive in terms of product development and the exploitation of process improvements can be damaging to profits at best and fatal to your organization at worst. According to Ledford, “Technological and scientific advances are coming to market more quickly, and the company that misses the window loses the pricing and profit premium available to market leaders.”

“So, how do we keep technology workers happy?”

In 2006, the global organizational and leadership consulting firm, BlessingWhite, conducted an extensive study and produced a report entitled, Leading Technical Professionals, which provides valuable insight into who these individuals are, how they operate, and what motivates them.

While it can be dangerous to generalize about a group as diverse as engineers, scientists, and IT professionals, here are a few of the most commonly desired career traits from the BlessingWhite study along with related strategies for improving job satisfaction.

Autonomy

Technology workers crave independence. They like to have significant control over their project content, work conditions, and pace at which they work. Not surprisingly, they do not appreciate supervisors who micromanage, and they appreciate being trusted by those they work for and with.

Manager’s Course of Action: Resist the temptation to control project details. Focus on what gets done, not how it’s done. Provide very precise direction in terms of project objectives, constraints, milestones, and timelines. Be clear about what you expect in terms of performance and anticipated results. Offer support and require reporting processes to be followed, but resist the temptation to over-manage the work process.

Achievement

Technical professionals are motivated by challenge. They like their skills tested. They take pride in their ability to solve problems. And they are often very driven, even obsessive, in their efforts to prove the value of their skills and intellect. Many technical professionals also want to have a sense that their work is meaningful. They want to know that their efforts are making a positive impact on the organization, their specific field of expertise, the chemical industry as a whole, and even to greater good of humanity.

Manager’s Course of Action: Challenge knowledge workers. Provide tough projects that may be beyond a team’s current skills, and set appropriate (i.e., realistic) deadlines. Help people to appreciate the impact of their work by providing context to their projects. And offer direct praise and recognition for each individual’s efforts and successful results.

At the same time, you must empower your technical staff to succeed by ensuring they have adequate resources and freedom from bureaucracy to focus on their work. Otherwise, you may become perceived as the quintessential manager from the Dilbert comic strip!

Keeping Current

Knowledge workers are motivated by learning. They view constant training as essential and feel a strong need to stay current on the latest trends and innovations in their field. Obsolescence is unacceptable—and a real threat to their careers.

Manager’s Course of Action: Provide formal and informal opportunities for learning and knowledge sharing. This can include classroom education, industry conferences, participation in technical associations, and even time to surf the latest blog posts. And don’t scoff when people ask to experiment with new ideas or technologies. Keep an open mind, and allow them to satisfy the creative, innovative, and inventive sides of their imagination.

Professional Identification

The BlessingWhite study found that “technical professionals tend to identify with their fields of interest or their profession first, and their organization second.” This can be a problem when an individual’s professional goals are not in line with the objectives or mission of the manager or organization.

Manager’s Course of Action: Create technical peer groups within your company that provide an internal resource for knowledge sharing and skill development. By building a “technical community” within your organization, you demonstrate your commitment to the professional development of technology workers in your organization while simultaneously reducing opportunities for unplanned attrition.

Better management. Lower Turnover.

While wages and benefits certainly make a difference, they should not be the core of your strategy to retain technology workers. Instead, focus on creating a great technical work environment, including the previously recommended tactics for providing autonomy, achievement, and career development.

And finally, don’t neglect the impact of management on retention. In our experience, the single greatest factor driving attrition (in all areas, not just technology) is poor or ineffective management. In terms of managing technical professionals, the BlessingWhite study offered the following recommendations:

- “Be leaders of people, not managers of projects.

- Understand what makes technical professionals tick.

- Be just enough of an expert to lead, not to do.

- Increase their influence outside of their team or department.”